Your period is my business

Right now, as you read these words, 800 million women are menstruating. It is estimated that almost 2 billion girls and women experience their periods every month, of which at least half a million do not have access to adequate resources or infrastructure to experience this time safely and with dignity. Menstruation is still shameful in every country of the world. Almost half of the schools in low-income countries do not have access to drinking water or toilets with running water. Due to their periods, girls don’t go to school, they skip an average of 10 to 20 percent of days (in some countries this may be 10, in others – 50). This translates into lower exam results, sometimes even dropping out of school, a poor start and poorer life opportunities. Ten years ago, Emily Wilson founded Irise International, an organisation that works to counter the inequalities that arise from the fact that girls and women menstruate.

How did you end up in East Africa?

I went to Uganda as a teenager and since then I’ve dreamed of going back there. During my medical studies, there was an opportunity to go to Kenya for research, right on the border with Uganda, on the other side of Lake Victoria. I was researching what prevented children from attending school. All the girls answered: period. That’s when I was struck by just how neglected this topic was. I had to talk to Kenyan girls to see how problematic menstruation was in my own context as well. And then it hit me: how was it possible that something we all experience could have been so systemically overlooked until now? I realised how blind we are to the health needs of women as doctors. Globally, the gender gap in what we know about women’s health and how we support their needs compared to men’s is striking. And it results from how we construct our world in general.

What does that mean?

If you look at research, for decades the default body tested has been the male body, and many studies have only been done on men. For example, in the UK, extensive research on heart attacks only included men, and yet it served as the basis for a treatment programme for both sexes; but when it turned out that heart attack mortality in women is much higher, it was considered inadequate. Since the 1980s, it has been said that male-only research cannot be used for women just like that, yet women who report symptoms different than those of men are still often misdiagnosed. In the event of a heart attack, this may concern as much as 50 percent of women! Or as another example: in the UK, one woman in ten has endometriosis. It takes as many as nine visits to the general practitioner to diagnose it, although it is a common disorder. 90 percent of the surveyed women declared the need for mental support, and none of them received it. Here you can clearly see how the entire treatment process fails because only women suffer from it. The approach that has been in place over the years has led to a massive neglect of women’s health and conditions specific to women. The period is one of them.

A year ago, I didn’t know what period poverty was. And that it isn’t just the lack of money for sanitary pads. Can you elaborate on this?

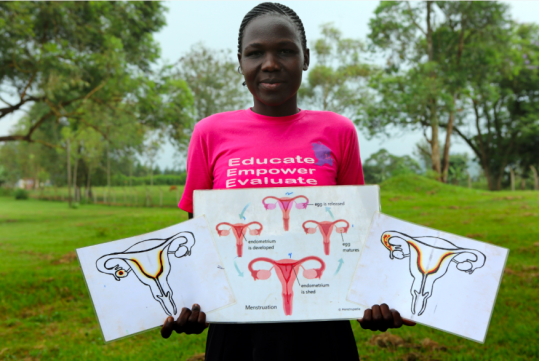

A handy and universal definition speaks of the toxic trio: lack of access to sanitary products, to information, and the stigma, taboo and shame. It’s difficult for a typical Ugandan or Kenyan girl to buy saitaryn products or have access to a bathroom and water at school. Oftentimes, very small things make a huge difference: a working lock in a toilet, clear and respected rules, e.g., that boys are not allowed to enter girls’ toilets or, when introducing reusable products, making sure that girls feel comfortable using them. Education is extremely important: many girls don’t know what’s happening when they get their first period, they are afraid, ashamed, they feel dirty. It is the stigma and shame that fuel the whole situation – they are the barrier that prevents discussing these matters.

Can you tell me about any one girl in particular?

Sure. I will tell you about Janine whom I met when she was a teenager, then she was a volunteer and today she is an advisor to Irise in Uganda. Before she got her period, she lost both her parents. When she felt the first painful contractions, her sister took her to her older neighbour, an herbalist. She told her: you will experience change soon, the body is preparing for the process, but she didn’t reveal what the process would be. She forbade her from taking painkillers because pain was natural, you had to bear it. She forbade her from talking about it to anyone. Janine obeyed because she was afraid. She had no money, she used old T-shirts instead of sanitary pads, there was no way to wash them, at school there were only latrines dug in the ground. With her heart in her mouth, she returned with the used package in her school backpack. “The shame of blood leaking through your skirt, boys calling you names, aches and infections, and many other things make you hate being a young, healthy woman,” she said. She called her period a monthly prison. Many of her friends wouldn’t go to school on those days, losing their only chance to break out of the cycle of poverty.

I was surprised that period poverty could also translate into underage marriages, the number of which has recently increased in Uganda due to the pandemic. How does all of this come together?

In Uganda, like everywhere else, the fall in income has hit women disproportionately hard as ever. Their lack of earnings affects the education and health of their children, but also the earlier marriages of girls. With the first period, they are considered ready to get married, when there is more income in the family, this decision can be delayed, and when there is less, the family treats marriage as a way to reduce expenses. Especially since girls cost more due to having to spend on sanitary products. In addition, Uganda has an accepted cultural norm that these products are financed by the sexual partner rather than the parent. So there is pressure to start a sex life, leading to early pregnancy, which in turn causes difficulties in continuing school, and early marriage. And while now, due to the pandemic, there is no school that would normally provide some protection in this respect, all these factors are pressing twice as hard.

Am I understanding correctly that since there is pressure to start a sex life, sex before marriage is not a stigma in Uganda?

It’s complicated. Of course, it’s a stigma. But at the same time, fathers are reluctant to pay for the extra costs for their daughters, so they let them marry or earn their own money. And if there is no way to earn money, there will always be a younger or older man willing to pay for products in exchange for sexual services. Many girls feel that this is the only solution available. Again, it’s a classic part of being a woman – getting conflicting messages and expectations. You are under pressure to behave in a certain way and at the same time you will suffer negative consequences if you do.

You’re saying that in order to start a change in the field of menstruation, it is enough to create the conditions for conversation.

That is why all our work within Irise is based on cooperation with local leaders, communities and leaders at the national level. Overcoming the barrier of shame allows for change. We want to remove it in the first place because when it is gone, girls are able to demand that their needs be met, and then the entire community, and even the government, become more open to these needs. Then social norms may change.

Do you really think so?

Of course! Look, if a government says: we’ll provide you with free sanitary pads, we’ll take action to make your menstrual experience better, it’s really saying: girls are important. And this is a truly transformative and empowering message in terms of gender equality. The government is saying, your period is not dirty, it is not your problem, as it prevents you from developing, it is a very important issue for us.

The UK government said this recently. You are part of the government’s Period Poverty TaskForce dedicated to ending poverty and the stigma of menstruation.

Yes, that’s great. However, everything has come to a halt due to COVID. Issues that should be considered crucial and important are still easily pushed to the background.

I have read the statements of the Ugandan girls covered by your programme. Absenteeism due to menstruation in the schools covered by the programme decreased by about 50 percent, and girls’ results in exams also improved. What else can you boast?

Directly, through educational activities, product support, mentoring, business support or a combination of all these activities, we have supported approximately 100,000 girls and young women. We also supported 100 non-governmental organisations by helping them include menstruation in their activities. Our greatest success is receiving the Power Together Award from the Global Women Political Leaders Forum in 2019 in Iceland, then we felt that our cause was important. We’ve been advising the Ugandan Government for seven years and recently started working with the UK Government. The Parliament has committed itself to deal with menstruation, and we have jointly developed standards for reusable sanitary products. Uganda in general does more in this area than many more affluent countries.

Myths and taboos related to menstruation are common. For example, in Poland, 21 percent of adult women still believe that they shouldn’t bake cakes during that time. It’s not much of a trouble, and it’s worse if they think they shouldn’t leave home, work, or touch anyone.

In Britain, a big elephant in a room that nobody talks about is menstrual sex: can we have it? You also hear: don’t use tampons, they will rob you of your virginity. There are plenty of these myths. It’s hard to tell if people really still believe in them, or if it’s just part of a discourse that strengthens the shame, stigma and control of the female body. Do they really believe in superstitions in Uganda, or is it just to reinforce the cultural message that a woman’s place is at home? All of these various beliefs are rooted in strengthening the traditional role: when you start menstruating, you become a woman, your role is to raise children. Though I don’t know what baking a cake has to do with that, you got me here.

You mentioned that little things make a big difference. You are dealing with change at the political level and at the same time ensuring that women can chose a sanitary product. Why is that important?

We always say that menstrual equality is about power, not just sanitary pads. If no women’s voices are heard in the space where decisions are made, bizarre situations arise. I read about a project in a refugee camp where a toilet was set up for menstruating girls. But this toilet was the only lit place in the camp, in effect it became a place for evening meetings of men, and the girls had no access to it. It all comes down to changing social norms, and greater representation of women and girls. Their voice must be heard. If you take care of it, everything becomes easier. We must have a choice during the period to feel dignity.

You said you see many things by looking across cultures.

Then you can clearly see the very cause of the problem, its root. We conducted an experiment: we quoted girls from Great Britain who had difficulty accessing sanitary pads, and girls in Uganda. Their experiences were indistinguishable to the audience. The idea is to equip women with the skills and knowledge to become advocates and leaders of change. For example, we help women in Uganda set up businesses related to the production and sales of reusable sanitary products, so far over a hundred have been created. This strengthens their ability to participate in decision-making at the local level, while at the same time removing the basic barrier that prevents girls from going to school.

How are your activities in the UK and Uganda different?

We are aiming for a world where the fact that you are born a woman does not stop you from realising your full potential. The flower of our activities has many petals: e.g., menstrual materials and facilities, access to reproductive health care, education, financial empowerment, security – many studies show that period poverty is both a form and a cause of gender-based violence. There is also a petal there about hearing women’s voices and giving them meaning. In East Africa, economic strengthening is the most important. In Kenya, a study found that one in ten 15-year-old schoolgirls had transactional sex in exchange for sanitary pads. In this context, financial reinforcement becomes critically important. Funds also allow you to travel to a local community meeting and devote your time to it at the expense of your daily activities and responsibilities. In the UK, on the other hand, we have a large network of young activists who we support in leadership because they feel their priorities are not represented in politics. Most of them cannot vote yet, but even those who can feel deprived of their civil rights because no one represents them. They work so that we don’t have to wait decades for something as simple as a period to end up in Westminster.

Before the government introduced hygiene products for all, one in ten British young women could not afford them and 50% of them skipped school one day a month. Period poverty is everywhere. There are also harmful and unconscious patterns of culture everywhere. For example, they told me not to tell my dad about my period. What did they tell you?

The first period is the moment in your life when society tells you very clearly what it means to be a woman. Of course, this starts much earlier – girls as young as six feel less competent than boys, and gender-distorted socialisation begins at birth. But when the period appears, all these social norms suddenly hit you. You are undergoing a transformation and everyone expects you to fit into the current form of femininity. I observe that at this point girls’ horizons shrink. Suddenly they realise how much harder it will be to achieve their dreams, they feel the difficulties starting to pile up because of their feminine identity. I also share this experience. I was a very active child, I loved running, swimming, I was confident. After I got my period, I became more sensitive to what I looked like, stopped roaming around everywhere, stopped swimming because my bathing suit suddenly felt embarrassing. The menstrual pain was excruciating and I was scared. I was afraid to wear white shorts, so I quit team sports. I don’t think I wore them until I was 30! Only recently have I felt that this is my body, I can wear whatever I want, and if I get it stained with my period blood, it’s not the end of the world. The period marks the beginning of the burden of being a woman – we share this experience regardless of the continent. And we want to lift this burden – yes, it might be inconvenient to bleed once a month, but that shouldn’t be something that prevents you from realising your full potential. Of course, poverty also plays a role here, but it is the cultural and social norms that put pressure on us the most.

What you say gives me some hope that we can build such a human, true connection between cultures, even now, in an age of extreme divisions.

I think we need to build global communities around our values that cross traditional divisions. I believe that all young women on the planet share the desire to live in a world where they can fully fulfil themselves. I am very excited that the topic of menstruation allows such communities to be formed and that I am part of it, I feel closer to my African associates than to the people in my traditional environment. Such communities break down inherited barriers, are more innovative, and can create new solutions.

Emily Wilson – the founder of Irise International, which works for menstrual equality and against period poverty in the world. A trained medical professional. The British charity initiative Founders Pledge recognises Irise as one of the most effective organisations in the world in this field. It works in Great Britain and Uganda, especially in the Soroti and Jinja areas, primarily for girls from rural areas and slums.

Author: Maja Hawranek

Photo: Tatiana Jachyra

The text was published in „Wysokie Obcasy Extra” a magazine of „Gazeta Wyborcza”

15 April 2021

KULCZYK FOUNDATION supports the activities of Irise International in Uganda. Dominika Kulczyk and her foundation will subsidise the "Rise Up" project, which aims to strengthen the independence of women and girls by solving the problem of economic inequality that underlies period poverty. Project beneficiaries will participate in business mentoring and training aimed to support the development of micro-enterprises dealing with the issues of period poverty and stigma. These activities will be combined with an online platform for mentoring meetings and a training camp for girls and women.