Blood into plastic

How did a postal worker come up with the idea to fight plastic in sanitary pads?

It started in 2018. At the time, I was a full-time postal worker in Cardiff. I noticed that a lot of bags and plastic are used to pack parcels, and that the amount of rubbish was increasing. It gave me something to think about because these were shipments only to residents of a few streets, so how much rubbish must be generated on a national scale! I decided to reduce the amount of my own. For example, by buying drinks in returnable bottles or used clothes. I was quite pleased with myself. And then my period started.

Did you start counting rubbish again?

Exactly. After a week, I noticed that there were a lot of used hygiene products that ended up in the bin. I clutched my head in disbelief. Before that, I didn’t think about what tampons and sanitary pads are made of. I did my research and I was terrified. Traditional menstrual products that I had used for years are 90% plastic!

When we think about polluting the environment with plastic, sanitary pads don’t seem particularly dangerous.

Exactly. We think of plastic shopping bags or drink bottles. That’s why I was so shocked. I was expecting cotton in tampons or pads. With my newly acquired knowledge, I decided to do something quickly. I wanted to find an alternative to plastic menstrual products. I went to the supermarket to buy the eco-friendly ones.

And?

It turned out that there was no alternative to plastic. And that really shook me. How can we make environmentally sound decisions if we, as customers, have nothing to choose from? I noticed that, yes, environmentally-friendly products are created, but by small companies, not powerful corporations. Then I decided to act. I had never been an activist in my life and I had never conducted such activities. But I thought: “Someone has to do it.” I decided to run an online campaign.

It is not easy to fight for something that is difficult to talk about.

Sure. It is easier to talk about plastic bottles that litter the planet than about sanitary pads.

Why did you choose sanitary pads?

Because no one had done it before. And menstrual products are used by half the population, so if they contain harmful substances, we should not be silent about it. When I told my friends about my discoveries, they were also shocked. And they also said that now they were ready to change their lives.

So, you don’t work at the post office any more?

For a year, I combined my activities with my full-time work. But the campaign is unfolding at an unprecedented pace and is taking a lot of time. I have learned a lot and am still learning.

What did you start the fight with?

First there was a petition. About 100,000 people signed it within a few months. Then I took the next step – I started using this support to convince decision makers, producers and sellers. There were more and more people who cared about this matter. We show the world what we mean via social networks.

In your petition, you write that menstrual products are produced in the billions, used for four to eight hours, and then thrown away. And they decompose for over 500 years. “That’s more than seven times the life expectancy of the person who uses them,” you alarm. “It means if Jane Austen had used sanitary pads, they would be still decomposing!” You’ve appealed to people’s imaginations. The petition has already been signed by over 240,000 people.

It is hard to imagine how much has changed in recent years. In my country, more and more is being said about menstruation, both in connection with period poverty and with the environment. It turns out that there are a lot of people for whom environmental issues are very important, so when we start talking about menstruation in an environmental context, it is also easier for them to talk about other issues related to menstruation.

When you started your activities, did you think about period poverty, breaking taboos, or did you focus mainly on the environmental context?

I was inspired by the success of Laura Coryton, who runs the online Stop Taxing Periods campaign to end the tax on menstrual products. But before that, I was not aware that menstruating people experience a massive amount of period poverty in my country and around the world.

How is the topic of menstruation and the environmentally-friendly approach to menstrual hygiene related to human rights?

It is unacceptable that menstruating people have limited access to hygiene products, that there is social exclusion, that they leave classes or are embarrassed, that their dignity is violated because they have periods. And when it comes to the environmental context, as people who want to take care of their planet, we should not be deprived of access to products that are not harmful to the environment. Such menstrual products exist, but not everyone wants them to be available. I have heard this slogan a lot: “The issue of menstruation does not concern me because I’m a man.” But it does! It concerns men because it concerns their mothers, wives, daughters, friends, and sisters.

It started with one petition. Now you are among the 100 most influential women in the UK.

I didn’t start my activity to get awards, just to share my views. In the beginning, the producers didn’t want to talk to me because I was alone. But when I gained the support of thousands of people from all over the world, I felt amazing. I know that I am going to do this forever. I don’t mean the menstrual issue, just the fight for the environment. I didn’t think that I would be attending important meetings and so many people would want to listen to me. Hygiene manufacturers are big corporations, but the problem is bigger than they are.

At first, I naively thought that I would come and say: “Get rid of plastic,” and the problem would solve itself. Now I know that it is a long process and that it is not just about plastic, but about showing people how important conscious shopping is – so that they buy less from producers who harm the environment and more from those who care about it. Because entrepreneurs often see the need to make change only when they start losing money. I try to convince producers to feel responsible for what they produce, and it is not necessarily only about intimate hygiene products. I am active in the UK, but I am wondering how to expand my activity because brands have an international reach. There is a global corporation manufacturing popular tampons and sanitary pads that is very resistant and uninterested in change. It will be easier if people from different countries put pressure on its management together.

What happens to plastic menstrual products?

Some end up in landfills or incinerators. I don’t know about Poland, but with us many people flush sanitary pads and tampons down the toilet. They go to the sewage system. It is not always possible to filter them out, so they end up in bodies of water and the sea. This way they often find their way onto European beaches. This is a serious problem because they break down into smaller pieces in the water. Plastic microfibres enter the digestive system of aquatic organisms. We think plastic harms whales and dolphins mainly, but traces of plastic from sanitary pads have been found even in the stomachs of crabs fished out of the Thames. Every year in the UK 1.5-2 billion sanitary pads, tampons and panty liners end up in toilets. According to other calculations, every second person who uses tampons or sanitary pads throws them into the sewage system.

In Poland, in many public toilets there are stickers reminding people not to throw menstrual products into the toilet. But they are not a sign of caring for the environment, but for the flow capacity of the pipes.

It’s still good that you pay attention to it. Unlike in Great Britain because even if there is a bin next to the toilet, it is usually not used.

Do you know how the plastic in menstrual products affects the health of the people who use them?

These products come into contact with the most delicate parts of the body. If I had known how much plastic ordinary sanitary pads and tampons contain, I would definitely have not used them. Accurate research is needed, but it is known that plastic can disrupt the endocrine system or cause cancer. Those who don’t use menstrual products also suffer the consequences of environmental pollution. For example, the residents of countries south of the UK where our rubbish ends up.

By addressing this difficult topic, you are also fighting period poverty.

When I started the campaign, I had no idea there was such a thing. Once I understood what it was, I wanted to find a good solution. I started the Eco Period Box campaign to encourage people to donate environmentally-friendly menstrual products to those in need. People from all over the country got involved in the campaign. Boxes for these products went to 20 stores in the UK and Ireland. The gifts were given to local charities. Last year, over six tons were collected! This is not a charity event, it is something each of us can do. Many people donate traditional pads and tampons, but we also want environmentally-friendly products to be delivered to those in need. It helps both those in need and the environment.

No matter where people come from and whether they are rich or poor, they should have a choice and decide what’s best for them.

What’s your greatest success?

Three UK retailers withdrew tampons with plastic applicators the production of which required more than 17 tons of plastic annually.

Regarding period poverty, I advised the Welsh authorities on what to allocate resources to. In the UK, schools are getting money to buy menstrual products for young people. Thanks to my intervention, half of the funds are allocated to organic products. And in five school districts, only environmentally-friendly ones are purchased. I am very proud of this.

What can we do to support you?

Talk to people, make them aware that there is such a problem. You can sign the petition at on Change.org/endperiodplastic if you like. It’s worth starting with yourself. I really enjoyed making changes to my own bathroom. Instead of shampoo and conditioner in bottles, I use those in bar-shapes. Instead of disposable cotton pads, I remove make-up with reusable wipes. I am vegan, I don’t use any animal products, and I encourage everyone to eat less meat, fish and dairy. I go shopping with reusable bags. I brew loose tea because express teabags contain plastic. It would seem that it is difficult to do something good for the environment on a micro-scale. But if it’s a lot of changes, even small ones, and if we encourage our family and friends to do so, there will be results.

Ella Daish - British activist and ecologist. She fights to eliminate plastic from menstrual products. She conducts legislative activities and talks with manufacturers of sanitary pads. She was on the list of people changing the world for the better (The Big Issue’s Top 100 Changemakers of 2020) and in the top 100 most influential women of 2019 according to the BBC

Author: Agnieszka Urazińska

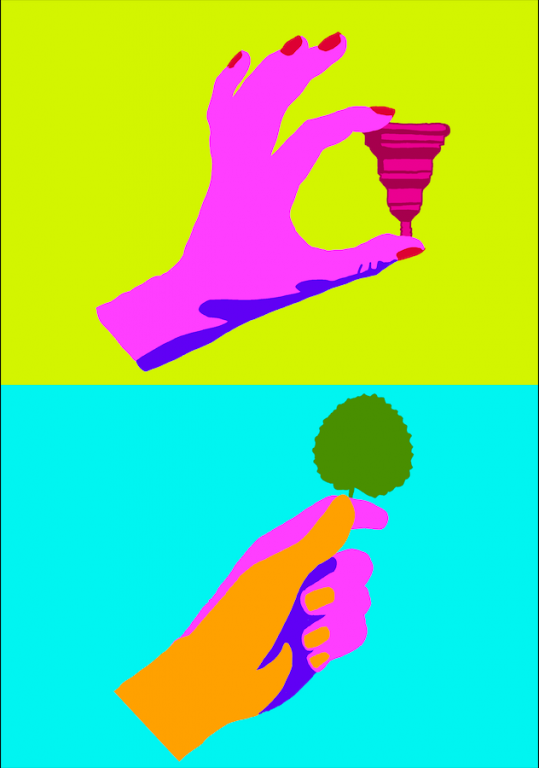

Illustration: Marta Frej

The text was published in „Wolna Sobota” a magazine of „Gazeta Wyborcza” on 15 May 2021