Embroidery and the feminine cause. Ewa Cieniak’s works bear traces of violence and rape

‘Women have always told me that I should be different than I am. Nicer. Less dishevelled. Less smart. Pretend to be stupid – they advised. I’m standing in the back. I see myself as the worst. A lump without a shape. On the verge of self-destruction that you can’t see. You also can’t see that one year I decided to disfigure myself, anoint myself with just a needle.... Irony. If I did the embroidery, the blood would be everywhere’, Marta will say.

Weronika: ‘Taking a raw nude photo wasn’t that easy, I felt like I was fully confronting myself in that good and bad sense’.

Aneta: ‘Accepting your own physiology is still difficult. Menstrual blood is still abhorrent, even though it is a harbinger of motherhood, love, adulthood, and beauty. When Ewa first showed me the sketches of the project, I was terrified inside’.

‘At the beginning of the year I was in such a moment that I really needed to meet women, I started to look for possibilities to generate events that would bring me their energy’, says Ewa Cieniak, the artist.

Ewa ends up in a circle organised every month by Maria Ela Ziemkiewicz in Warsaw. Dozens of women strangers, a safe space to voice their stories. At the same time, she discovers Liv Strömquist’s comic book about periods entitled ‘Fruit of Knowledge: The Vulva vs. the Patriarchy’.

‘I started to wonder if I was ready to consciously and openly talk about it’, she says.

She has an idea for a project. The impulse is the competition for the Triennial of Tapestry in Łódź. Through the eyes of her imagination she sees naked women. She doesn’t know where to find them or how to invite them. She thinks about changing their faces. ‘These strange concepts were born out of internal resistance, out of fear and apprehension as to whether anyone would agree to participate’, she confesses.

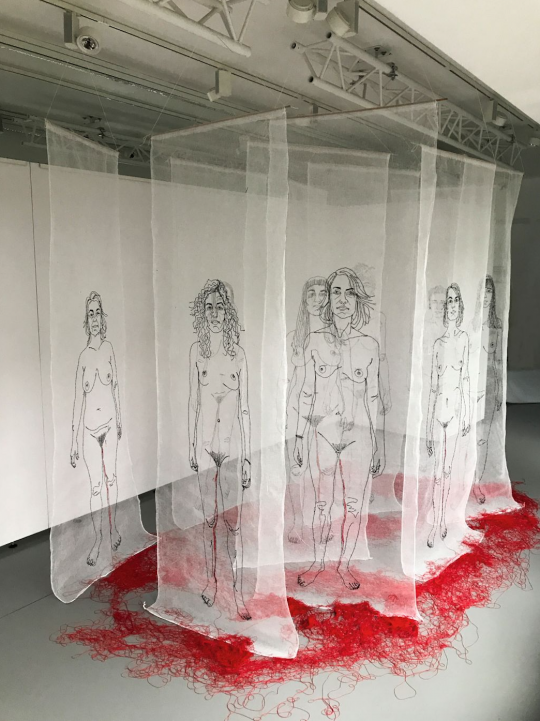

She publishes a post on her Facebook. She chooses 10 women – just because of the time she has until the Triennial. She gets a nude photo from each of them. She takes some of them herself. She uses an overhead projector to transfer the outlines of their bodies onto three-foot pieces of gauze. She uses only two colours in this work. Black for sketching and mapping. And red to show them in a cycle, connect them. A red trickle of blood flows from between the legs of each of them. Red threads tangle on the floor.

She plans the embroidery installation so that the women are looking at each other, interpenetrating each other. She will call this work ‘Synchronicity’.

When she shows them her embroidery, she hears:

‘I was incredibly impressed by the sight of naked, bleeding and joined bodies’ (Olga).

‘After seeing my image embroidered on gauze in the company of other women, I felt safe. We should all feel this way about our physicality’ (Weronika).

‘I believe in the power of ritual, that when we as women stand together (...) our strength grows, but also our wounds heal’ (Magda).

‘“Synchronicity” is sisterly and communal (...) I sat and looked at her sketches and overcame my shame. I thought it was important that other women should also look at themselves with love (...) I feel happy to be part of this women’s circle’ (Aneta).

Women’s voices are as important as embroidery here.

‘I felt more confident in dealing with subjects that aren’t easy and aren’t pretty, nor are they just portraits as my previous projects’, says the artist.

It’s the first time she’s operated with a completely undressed figure. She’ll take it a step further in her next work.

‘Synchronicity’ was more black than red. ‘The Shroud of Mariupol’ reverses the proportions, it is more red.

THE SHROUD OF MARIUPOL

It’s April. It is then that she will learn about the tragedy of the rapes in Mariupol.

‘I was shocked. I was driving my car at the time. I sobbed, thinking about what happened there. And a little while later I still had that shroud in my head’, she says.

‘“The Shroud” is not only embroidered, but painted with your body’, I note.

‘Yes. I was the material here. I encountered resistance within myself. It comes up every time I have to cross something. The theme of the shroud – both the subject and the form – made me uncomfortable, but I also consciously waded through my own discomfort to get to what was important to me. I felt I had to and wanted to do it. I walked into a quilt store on my way to my mum’s. I stood next to it and felt that this was the material I wanted to make the “Shroud” on’.

She covers 80% of her body with red paint. She leaves its reflection on the material. She embroiders. She marks symbolic traces of violence and rape. She uses foil that restrains the victim’s wrists. Wrapping her head around like a halo. It’s Tuesday. On Thursday, everything is ready. At the same time, several dozen women will stand in front of the Russian embassies in Tallinn and Gdańsk with plastic bags on their heads, their hands tied behind their backs, and their panties smeared with red as a gesture of solidarity and defiance. There will be red paint running down their bare legs. These silent protests, like photographs of already dead bodies, stay in the mind.

Ewa Cieniak hangs a quilt on the fourth floor of a tenement house on her balcony opposite the Church of the Holy Family of Nazareth in Warsaw. Ukrainian flags hang on many balconies at the same time. The quilt is four meters long. The performance is short-lived. Just long enough to take a picture. She doesn’t know how many people manage to see it. The impervious material obscures the downstairs neighbour’s window.

GRANDMA NASTKA’S PILLOWS

Ewa Cieniak has been embroidering for three years. It’s because her late grandmother’s Nastka’s pillows.

‘They were kept by my mother. I didn’t know very much about them. Grandma sewed dresses, pillows. I brought them to my house once. They were lying on the couch. One day I started painting her portrait, out of longing. I looked at the pillows, picked up the thread and started embroidering the portrait. I saw that I really liked the time-consuming nature of the process, that the content was slow to arrive here. I began embroidering extensively on small formats and canvases, still quite traditional at the time. But I kept looking. I experimented with form and colour – embroidering with white thread on white. With me everything happens out of curiosity’, says the artist.

That’s how the portraits started, with lots of threads sticking out of the canvas, layering up.

‘While threads offer great opportunities to compact the space, I found myself saturated with canvas. I was intrigued by foil. Whether or not it would break, because if it does, this material gives you the opportunity to see the guts. And in embroidery – and this is what delights me most – we can treat the left side equally to the right. Using foil allowed me to introduce water themes into my work’, says Ewa.

This is how bathtub portraits are created. Then she uses gauze.

‘I thought I would see what was on the other side, we would all be in it together, simultaneous and visible. Also, this material is very much related to menstruation. I checked the price of a hundred meters. Gauze was so much cheaper than foil! I can tell that it showed up a little bit out of cheapness’, she says.

Ewa offers a workshop that is a circle. 15 women embroider their portraits in Warsaw.

‘We shared our stories. There, even silence was important as much as commenting on what comes out from under the needle. In the beginning I hinted at how to start the process, then each participant already knew what she wanted to do, and as a result each piece is different’. These embroideries capture each girl’s character. It’s easy to see the diversity in them.

A meeting planned as a one-time event becomes part of a larger project. You can embroider together with Ewa Cieniak on 22nd May during workshops included in the Łódź Design Festival programme.

‘That gave me courage’, she says. ‘In the beginning, I didn’t dare to think of myself as someone who was leading such a project, that it would be an initiative that would travel around the country, and that perhaps by the end of the year I would gather the experience of ten meetings and there would be 10-15 portraits in each of them. It still gives off a lot of collective energy. Feeling empowered as a woman motivates you to take on challenges. Just like me’, Ewa adds. ‘I use it a lot’.

Author: Anna Berestecka

Photo Private archive of Ewa Cieniak

Ewa Cieniak with her work embroidered on foil

‘Synchronicity’ – embroidery on gauze

‘Shroud of Mariupol’ – embroidery on quilt

‘Shroud of Mariupol’ – detail, embroidery on quilt

‘O_Krąg’ – embroidered self-portraits made by participants of workshops led by Ewa Cieniak

The text was published on wysokieobcasy.pl on 21 May 2022