A mother’s identity

I have recently talked to a professor of gynaecology, who told me that she rarely has patients who are happy with their pregnancy. Is this anxiety new? Bigger than it used to be?

On the one hand, women now have more courage to show what they feel, including fear. On the other hand, many of us are afraid about whether we will be able to get pregnant, and when we do, whether the baby will be healthy. This fear is the result of knowledge: before we get pregnant, we start taking folic acid, we have ultrasound or genetic tests. But this is the outer, rational layer.

And what’s underneath?

Control. On a daily basis, we derive a sense of security from predictability, control and influence. When we get pregnant, we realise that something is growing inside us, something uncontrollable. Our bodies are changing and there’s nothing we can do about these extra few pounds that we all hate these days. We lose control over it.

Our loved ones want to help and they say: “So many women have given birth before you”. Or: “This is a perfectly natural situation”.

W ciąży jesteśmy same. Nawet jeśli mamy bardzo zaangażowanego partnera, który nas słucha i jest uważny, to mimo wszystko doświadczamy tego stanu same.

We’re alone when we’re pregnant. Even if we have a very committed partner who listens to us and is attentive, we still experience this condition on our own. Mums say: “You’re better off than I was anyway”. Partners would say that, after all, your sister or your friend gave birth – as proof that women who have been through the same thing are close and everything is fine. But the truth is they’re all scared, too, and they don’t really know how to help. They often have a sense of helplessness and thus also want to reassure themselves. Because childbirth is a borderline situation between life and death, it is an unknown and this nine-month tension needs to be relieved.

When I was pregnant, I had strange dreams, nightmares, fantasies. I felt as if I had no control over my imagination. My loved ones told me: “Don’t worry, it’s hormones”.

These were your childhood memories, your grandmother’s and mother’s stories that you have memorised, their childbirth traumas. But it’s also the result of how your mother gave birth to you, how she experienced giving birth, how she took care of you and raised you. It all stays with us.

Why does it all resurface when we’re pregnant? If I wanted to have a baby, why so many dark thoughts? Why do I treat it like some kind of parasite growing inside me?

This is the result of anxiety. Most often – that we’ll be seen as bad mothers. And we pass that fear on to what’s inside of us – the future child. They are a threat, a parasite, as you said. When we’re afraid, we can also look for threats in doctors, suspect that they are incompetent, that they want to deceive us, that they will not take good care of us or the baby, that hospital births are terrible, that they will certainly not see to something, that they will force us to do something, or leave us without help. Look at what happened when family births were banned because of the coronavirus.

Women fought for their rights. They quoted many specialists, the WHO and other institutions. They documented it really well.

Because they focused on the fight, they channelled their fears. And, of course, that’s a good thing. Women have the right to fight for their rights.

But let’s think about the mechanism itself. When I fight, I concentrate on removing difficulties, I do not reflect and I do not think about difficulties themselves. It alleviates my own fears a little because I can focus on an external enemy. Plus, I’m often looking for allies so I’m not alone anymore.

In psychotherapy practice, we hear all sorts of stories which uncover these transferred feelings. In order to be less afraid, we might start seeing our mum or mother-in-law as an enemy. Women are afraid that their mums will visit right after they give birth and lecture them, that they will take the child or, on the contrary, leave them on their own.

It can also be focused on the partner, friends, other people, on the bad world.

How can my experiences as a very young child affect what kind of mother I am – good or bad?

Melanie Klein, one of the creators of psychoanalysis, claimed that there are two mothers in the child’s mind: the good one that has a smooth flow of milk and is always there when the child cries, and the one with an empty breast that goes to the bathroom and runs late, does not come immediately when the child begins to cry. There’s even the term “good breast” and “bad breast”. A child can’t merge those images of a mother into one, which is why they see either the utterly good one or the utterly bad one.

This debate about bad mothers and good mothers is going on all the time: in conversations with friends, in the media, in the culture. As mothers, we also tend to define ourselves that way – we are either good or bad.

Meanwhile, as the child grows older and starts connecting facts, their image of us becomes more and more comprehensive. For example, they can see that their mother has interests besides caring for them. She’s on the phone, the child pulls her hand, and the mother says, “I’ll be right back with you”.

Do you remember that from your childhood?

Of course.

The child then experiences frustration, feels abandoned, separated. They start fantasising about going back to their early childhood, to their mother’s womb.

Psychotherapist Melanie Klein said that a lot of kids’ games manifest this. That’s when girls begin to wonder where they came from. When they find out that their mothers carried them in their bellies, they imagine themselves having a baby in their bellies.

That’s when girls start to identify with their mothers. If at this stage the daughter receives a lot of positive messages and is accepted, then as an adult she is more likely to admit: “I want to be a mother”.

Although our desire to be a mother may also result from the fact that in our teenage years, we used to compete with or envy our mothers.

So the way we are as mothers is determined by what we had as children.

It sure is. In everyday life, we don’t have time to think about how our childhood has shaped us. We grow up, settle down, get a job, start relationships. We think about whether our partner is going to embrace us, not the way our mum used to do it when we were little.

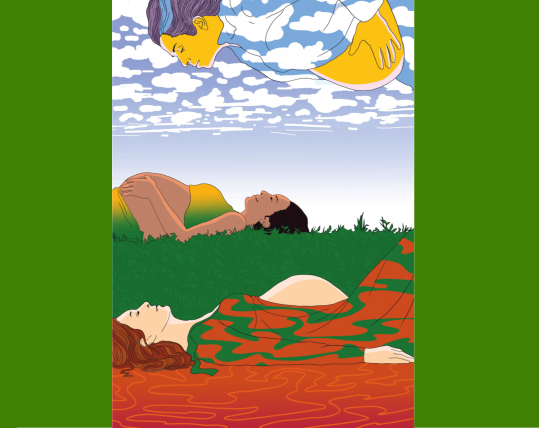

Pregnancy is being at a standstill. A dam with early memories opens up and sometimes we are literally flooded with what we carry inside. It can be good, but it can also be bad and painful. We can run from it or accept it.

What does pregnancy give us? How does it change women?

It allows us to get to know and understand ourselves better. We experience conflicting feelings. It changes the way we think about ourselves.

You have to go a long way from being somebody’s child to being somebody’s parent. If we accept what is behind the dam of our childhood memories, if we embrace and accept them, we will understand ourselves and our lives more fully and deeply. This could be a moment of identity building, maturing and becoming.

Most of us are shaped by our response to what our mothers were like: “I want to be like her” or “I don’t want to be like her”. We consent to our femininity and embrace our resemblance to our mother or we experience disapproval, despair, pain and anger. Pregnancy is an important moment in identity building. The question “what kind of mother am I?” conceals many others: what kind of mother I had, what kind of life I had as a result, what I was equipped with, what I was lacking and who I am today. Sometimes we need specialist help in this process.

However, there are always people, including many women, who believe that pregnancy and motherhood must be affirmed and raved over. They can’t accept the fact that it can also be traumatising.

We live in times that require perfectionism. We try to make a good impression, as if we are organised and perfectly prepared for anything. The idealisation of motherhood reveals a desire to repair. Maybe women who depict it that way or create such façades lacked their mothers being present in their lives? And they’re processing it in a substitute form of lack of dresses and beautiful objects. These women often say: “I envied my friends because their mums took good care of them, dressed them nicely”.

If we don’t look inside ourselves, we may not know that what we’re experiencing is in fact longing for our mum. And that’s when we put bows on our kids’ heads and have overstylised photo shoots in wicker baskets. There’s a desire to make motherhood look perfect.

I know a lot of women who, after giving birth, get into eco movements and home births. They’re looking for a connection with nature on an almost shamanistic level. Sometimes it’s filled with idealism. We become part of nature, we rediscover it, it’s pure goodness.

Pregnancy connects us with nature. For some people, it is something that brings relief from responsibility. We confide ourselves to another mother – Mother Nature.

But, paradoxically, it also implies control: I will not give birth the way the midwife tells me, I will do it my way, the way I consider best, I won’t throw myself at the doctor’s mercy.

We are very afraid of aggression and childbirth is an aggressive act of pushing out. For people who do not accept their own aggression, childbirth may be a very difficult experience. But aggression related to childbirth has good consequences. We need to push the baby out of the belly – that’s constructive aggression.

The child also has such aggressive gestures, they want to preoccupy the parent, take over the mother’s entire breast and appropriate her life.

Sometimes I get the impression that we, as a society, have walked out on our therapist halfway through our session. It occurs to me when I hear: “What do you need a child for? Aren’t you afraid you’ll traumatise them, that you’ll be that hated, unsympathetic, hurting parent?”

Yes, people have read “Toxic Parents” by Craig Buck and Susan Forward, but they don’t want to look inside themselves for what they see in their parents. Growing up is when you can admit that your mother was right about something. When we become parents, we start to sympathise with ours. But of course, understanding doesn’t always mean justifying.

When a child is born, friends often hear: “When are you going to get back to life?” Friendships end.

We’re back to the issue of what we’ve had in the past. How did we process our childhood, our parents?

Everyone reacts differently to seeing a mother with a child. Sometimes we get emotional because it brings memories of our own motherhood that was difficult sometimes – we identify with the mother. Sometimes we identify with the child and their desire to have a perfect mother that never fails. Sometimes we envy the child as if they were our younger sibling – that’s when we’re likely to say that the child is spoiled and ill-mannered. We might also feel a desire to compete with this mother – it may be a friend of ours, our client, patient, our student’s mother, etc. – that’s when we’re critical, we want to save the child and we think that we would be (men can feel the same way) a better mother. Of course, the basis for these feelings are our own childhood experiences and how rooted they are in our psyche.

That’s why it is so important that people professionally involved in helping young mothers or young parents are aware of their emotional baggage and which of these responses they tend to have.

In training in psychotherapy, we pay particular attention to this because the ability to listen and offer support without judgment is a basic skill necessary to effectively help parents and their children.

But these tendencies to different reactions can also be observed on the streets, in parks, cafés and in families. For example, we’re feeding in the park, and some lady says to us, “Why is that baby hanging on that boob?” Or our partner keeps rushing us when we’re in the toilet and the baby starts crying, or vice versa – he suggests that you can react more calmly to crying and not stress about it. Let’s remember that people who comment on how we behave are often talking about themselves.

But such comments still hurt. After every column I wrote about motherhood and about feeling excluded, I got messages from women telling me how hurt they felt, how judged they were. Facing the outside world with a child is painful.

The more insecure I am, the harder it is for me to endure such remarks. And the higher the risk that the lady in the park commenting on our way of feeding will ruin our day. And yet you can tell her: “Did you know that this is what doctors are recommending now? This is how babies are fed these days. You must have fed your kids only according to a schedule, am I right?”

You might end up having quite an interesting conversation. But in order for us to respond in this way, we need to know what we are doing, why we have chosen to do so, and have confidence in our own competency.

We also need to be able to handle our own doubts. Usually such comments from friends, family or even strangers bother us because we are not confident, we are in the process. We’re dealing with the issue very organically. We’re devitalised, tired, insecure, overwhelmed with doubt.

A journalist friend of mine asked me when I was going to get back to serious topics and stop writing about pregnancy and babies all the time.

Did that hurt you?

A bit.

Because this is one of the greatest fears that women have – fear of being out of circulation. Of being excluded from society or anything else. Sometimes it’s combined with ambition. It is difficult to admit, even to ourselves, that we don’t want to read Tokarczuk because now we’re analysing adding new ingredients to our baby’s diet.

Are we really excluded or do we just feel that way?

Surely women have always experienced this when on maternity leave. Away from work, from the everyday rush, at a standstill. In our practice, we often hear about waiting for a partner to come home from work to find out what’s happening in the outside world. My friends went to training, got promoted, and I can’t. I can’t even walk down the street the way I used to because I have a stroller or a carrier. It is difficult for women to give up on being part of a world in which they used to play an important role. Sometimes it’s possible to reconcile motherhood with this world, sometimes it’s not.

When we experience exclusion, we tend to demand that the world adapt to us. It’s not always possible, we are excluded for some time. It can get very frustrating. We don’t tolerate loss. We deal with it in therapy.

Why does this bother us so much? We’re fulfilled as mums but somewhere inside we feel bad that other people meet up in town. And sometimes we’re embarrassed to admit it. Because then it seems like we want to be in two places at once.

We should have acquired this ability when we were kids, but it’s really hard. It’s the ability to temporarily exclude and be temporarily excluded. For example, if we can’t stand the fact that our baby is lying alone for a while or is sleeping in another room and we worry about how they feel, we think that it must make them upset and it does not allow us, for example, to have sex or pursue other leisure activities of our own, then it is an issue to work on in psychotherapy.

These thoughts can also come up when we get pregnant for the second time and we worry whether the first child will be able to handle it or forgive us.

A czasem nie zachodzimy w drugą ciążę, żeby nie ranić tego pierwszego dziecka. Rezygnujemy z marzeń o większej rodzinie, bo wykluczenie, którego będzie musiało doświadczyć pierworodne, wydaje nam się nie do wytrzymania.

Or we don’t get pregnant for a second time so as not to hurt the first child. We give up on our dreams of a larger family because the exclusion that the first-born will have to experience seems unbearable.

Exclusion or feeling excluded is also experienced by women who don’t have children. Because they don’t want to or they can’t.

People choose not to have children for a variety of reasons. The experience of developing something, completing a project: publishing a book, creating an organisation, painting a picture, is like pregnancy, childbirth and having a child. Fortunately, social tolerance towards women who deliberately give up motherhood is growing. We need to remember that there is such a process as sublimation, i.e. not fulfilling desires directly, but processing them in a constructive and creative way. Such a concept, as I understand it, is behind the institution of celibacy in the Catholic Church. Paternal and maternal functions are performed towards the believers.

We spend our whole lives dreaming about the perfect mum and we often experience trauma because of it. But when we have a kid of our own, we want to be perfect, too.

Winnicott said that a mother should be good enough.

The perfect mother doesn’t give room to frustration. And frustration – in the right proportions – can be constructive. We wouldn’t have learned to walk if someone was constantly passing us the toy we wanted to grab. What forms us is the experience of lacking and discontent. If we lose ourselves in dreams of our own perfection, there is a risk that our child will not acquire resistance to frustration or perseverance in pursuing and trying.

On the other hand, if there is no experience of being able to achieve something, to grab and take something for yourself, then the sense of agency and the belief in your own success may tail off.