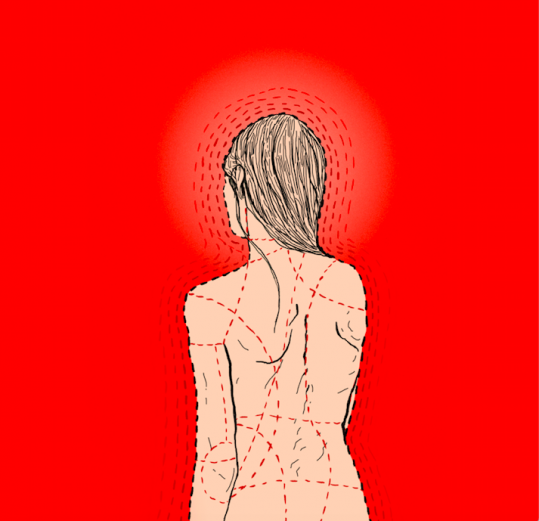

Even 10-year-olds are saying they’re too fat, 12-year-olds are beginning to starve themselves. Anorexia is often a rebellion against femininity

I have recently heard about a 13-year-old girl who had started a drastic diet a few months ago. She decided to eat 400 calories a day. She started to lose weight at an alarming rate, her parents didn’t notice anything, they have only realised recently, completely by accident.

Because children’s decisions like that can be overlooked. Especially when parents are overworked, busy making money for the household and don’t have time. And when they don’t pay attention to how much the child eats, to whether the lunch the child took up to their room didn’t end up in the bin.

However, there are signals that are fairly easy to read that show something is wrong with your daughter. I say “daughter” because boys are much less affected by this problem, although they are to some extent as well.

What can be the first sign?

The most disturbing signs, the most typical symptoms that can tell us about an eating disorder, are a heavy focus on food itself. A kind of general preoccupation with food: following various diets, browsing forums, newspapers, all this is connected with the obsessive thinking about nutrition and doing various activities surrounding it. It’s about talking about food and eliminating often specific, successive products. A person with an eating disorder focuses on their times of the day, on what they are eating at those times, and on the specific meals they begin to construct for themselves. They have set times when they have to eat: it is similar to obsessive neurosis in which the patient must perform obsessive rituals to prevent an imaginary misfortune, but here the behaviours are specifically about food and controlling it.

Sometimes girls throw away breakfasts, lunches, dinners prepared by their parents, don’t eat them, avoid sitting at the table together, lock themselves in their rooms, eat alone, cheat. They isolate themselves from the rest of the household, and their only safe companion becomes the disease. Vomiting after meals, characteristic of bulimia, and excessive physical activity are also undeniable signs.

There is also a kind of illusory thinking about various things related to food: that is, there are certain myths associated with anorexia that girls believe in, because they often create them themselves.

Like what, for example?

Misconceptions and fears about food, e.g., if I put my yoghurt in the fridge next to my parents’ butter, the yoghurt will get “infected” with calories and become fatty. Other myths associated with anorexia concern the rules of constructing meals to prevent weight gain, e.g., not eating after 6 pm or avoiding breakfast. Girls believe these myths because they often create them themselves, but some of them are also due to ignorance, lack of proper nutrition education and the informational chaos offered up by the media, promoting a multitude of fancy diets.

These myths also apply to dairy, lactose or gluten, there is plenty of information about how harmful they are, or that carbohydrates cause weight gain so you should eliminate them. Generally, chaos and conflicting messages cause people to pick and choose information from individual myths, the kind that suit them. They often also create them themselves or develop them in response to what I believe to be erroneous specialist recommendations. I remember my psychiatrist telling me, as a 12-year-old, to keep a detailed food diary and confess what meals I ate. I had to measure and weigh my food so the doctor could keep tabs on my menu. A theoretically harmless recommendation led me to absurd obsessions. I wrote down the diameter of a pancake, I used a compass to measure the size of dumplings, I could only eat slices of bread measuring 5 cm by 8 cm, and I didn’t eat any dishes that were difficult to verify. At the school canteen I started to feel like a freak, I was afraid of unpleasant comments from my peers, so I avoided company and food.

What other signs can indicate an eating disorder?

Social isolation, cutting oneself off from loved ones and friends, concentrating, e.g., on studies and a perfectionist approach to tasks are the “norm” among people suffering from anorexia. When it comes to lessons, girls with eating disorders are very meticulous, disciplined, place a high value on their knowledge, school success, career, they control their behaviour and don’t allow themselves to fail or relax. They demand a lot from themselves. They openly express hatred for their bodies, exaggerate about their dimensions or excess weight, which in most cases they don’t have, but they maintain the belief that they are fat. They constantly compare themselves to others. Repressed anger (because, after all, exemplary girls are not allowed to be angry) is directed at the body. They hate it, they think they have “fat” legs, for instance, they try hard to fight it. The image of their own body is distorted, the lack of self-acceptance grows.

Is all this because of social media?

Partly at least. There are conflicting messages coming at them from the media in general. On the one hand, they read and see pictures that talk about body acceptance, and on the other hand, they have adverts that promote miracle diets and celebrity six packs. Social media further feed the obsession with appearance, which is then linked to how girls and women treat their bodies.

The body becomes an object.

You monitor yourself all the time, paying constant attention to what you look like. Selfie culture is almost an obsession that didn’t exist before because there was no Facebook or Instagram.

In Poland girls have the lowest self-esteem in Europe, they feel constant pressure related to what they should look like. As many as 81% don’t have high self-esteem. The only place where it’s worse is Japan, where as many as 93% of girls don’t think positively about their bodies.

The data and the reports are indeed shocking. Even 10-year-olds talk about themselves as being “too fat”. And worst of all – that’s what they think. These are all horrifying reports. 13-year-olds are buying laxatives from pharmacies without knowing anything about them. It’s hard to have an objective view of the value of such preparations if we’re bombarded with them on the pages of magazines, with such a message imposed on us by the media that we are constantly not good enough, constantly supposed to slim down. Paradoxically, people who respond to this message aren’t actually fat, but are socially sensitive to these kinds of statements indicating what they should be in order to be accepted.

Adolescent girls are definitely sensitive to these messages.

And they equate success and self-esteem with what they look like. This is very consistent with the canon imposed on women, in which certain features and behaviours are inscribed, because the whole thing is also about how we should behave, what we should do and what social roles we have.

What percentage of girls suffer from eating disorders: bulimia, anorexia, orthorexia?

A report of the Centre for Education Development shows that anorexia nervosa occurs in 1‑2% of people. This doesn’t only affect girls and young women, because children and adults also suffer from anorexia. About 3% of girls and young women suffer from bulimia.

Unfortunately, the increase in the mortality rate resulting from eating disorders is growing. Few people are aware that anorexia has the highest mortality rate among all mental disorders. Of course, death is linked to cachexia on the one hand and suicide on the other.

If a parent picks up on the worrying signs, what next?

Since the problem affects a lot of aspects of life and functioning, an interdisciplinary team of people is needed for treatment. This is very important. First of all – a psychologist, a psychiatrist. But eating disorders also require medical care, if only to monitor the rate of weight loss and what is happening to the person. The disease destroys the entire body, hormonal problems often appear, the help of an endocrinologist and gynaecologist is necessary. I believe that it’s also important to be under the care of a dietitian who helps in nutritional education and dispelling all the myths that a sick person creates for themselves due to information chaos.

What do eating disorders stem from?

From the emotional difficulties that a person is going through. From life situations, low self-esteem, depression, from anxiety, fear of challenges in school or personal life. In girls, it may also be related to puberty and hormones. Every case is different, really.

Among the causes of eating disorders we also find an unstable, chaotic environment or excessive control and demands from parents. In an attempt to regain influence over their own situation and striving for autonomy, the person focuses on their own body and food, because that’s what they have the most control over. A child reacts in a similar way with their body. By refusing to eat, crying or stamping their feet, they express their opposition and their own will. Eating disorders also play a role in the self-regulation of emotions. Anorexia often “intoxicates” with a lack of energy, making it easier to anaesthetise feelings. A similar mechanism occurs in bulimia or compulsive overeating. It’s easier to throw up your anger than to resist your parents. We try to fill the hole in our hearts with chocolate because it’s safer than a boyfriend’s taunts or an argument with a fiancé. Unfortunately, this avoidance strategy doesn’t work for long. It in no way solves life’s problems and only makes the disease worse.

I would definitely suggest looking for causes – I know it’s obvious, but not easy at all. We should remember that anorexia, for instance, often appears as a rebellion, a hunger strike in which there is an inherent disagreement with certain life situations, very often an overload or events that exceed the possibilities of coping with stress. It can be rejection, heartbreak, etc. Puberty could be another. Some girls don’t accept the changes that are beginning in their bodies. They don’t like them.

Does menstruation play a particular role in the way a young girl who already suffers from anorexia nervosa, for example, perceives her body?

Not just menstruation but femininity as a whole. With adolescence comes the development of femininity, a moment when maturing individuals discover a different meaning of being a woman.

That is?

They learn what social role a woman plays, what norms we have imposed on us, what a woman should be like. From a sociocultural or feminist perspective, eating disorders are said to be a rebellion against what the culture imposes on women: think of the role of the obedient, polite, pretty, absolutely amenable girl who has to take care of the house, then her husband, bake cakes, while she herself should most definitely eat sprouts under the pressure of what she should look like and how to meet cultural requirements.

They say that anorexia, for example, is a kind of strong attempt to fit in with what culture expects, and on the other hand, it is a rebellion against it. By refusing food, we refuse love and all that is offered to us.

Going back to puberty, what kind of patterns a girl has when it comes to her mother’s behaviour is important. Because from this she learns how to be a woman, what expectations others will have of her.

She watches her mother and her attitude towards her body, listens to how her mother treats herself. She creates an idea of femininity.

If her mother doesn’t like her thighs or her breasts, the girl may not like her own either.

This affects her psychosexual development and how she perceives her physicality, breast growth or the first years of menstruation.

Some girls don’t accept these changes, growing hips and breasts and they would like to go back to the figure they had before.

Eating disorders can be an attempt to stall this phase. Of course, not every adolescent girl doesn’t like her breasts, which is why I said it’s a form of demonstration, a defence against entering the next stage of life, one we don’t agree with.

Entering into social roles?

Yes, and that comes with sexual fear. When it comes to eating disorders, there is a kind of fear in some girls. A fear of harassment, for instance. Girls receive cultural messages that being a woman entails a lot of risk. So there are negative feelings towards the development of the body, and it is associated with fear.

Does menstruation disappear with an eating disorder?

This is one of the first diagnostic criteria when it comes to anorexia, for instance, because it is associated with hormonal problems and they’re primarily related to menstruation.

Do girls who face eating disorders experience the absence of menstruation as a relief?

Sometimes this is indeed the case, but paradoxically more often they want it back because it is a motivating factor in recovery. Maybe it depends on the stage at which the person is, because in the first phase of the disease health is what’s overlooked, girls in the early stage do not realise the health consequences. Health is not valued as long as it does not entail visible limitations, associated with pain, with performing various activities or with disorders spiralling out of control, be it just some hormonal changes, such as hyperthyroidism or insulin disorders, i.e., slowing down of the entire metabolism. Infections and inflammations are common, and osteoporosis is also associated with nutritional disorders and hormonal changes. It’s surprising, but young girls can have osteoporosis and menopause due to changes in their physiology.

And the very absence of menstruation – at the beginning of the disease – is evidence that the rebellion is developing, so what the girl is manifesting is somehow succeeding.

Girls who suffer from an eating disorder and whose menstruation has stopped take it as a relief because they feel they have stopped the development of this unwanted, undesirable femininity? Is a boyish figure the ideal?

When you talk about a boyish figure, it occurs to me that it can be like a kind of model, so to speak. People who suffer from eating disorders may try to identify with a boyish appearance because boys and men are allowed to do more. Because of their role and gender, they are privileged. Consequently, this attempt at identification is also cultural. I think the most important thing is to publicise the problem, talk about it and not avoid it.

Is this why you started the Głód(nie)Nażarty Foundation?

I’d been thinking about it for a long time. I published a book many years ago, back in high school, called “Dieta (nie) życia” [Diet of (No) Life], it’s my personal story. Back then, I got a lot of phone calls from parents, girls, grandmothers, people I knew with eating disorders. But the strongest response was from people who were looking for help and reliable sources, which are sadly lacking. I once saw a website where girls suffering from anorexia – children – were raising money for their own treatment. I thought it was terrible that children were doing it, that it shouldn’t be like that.

The state isn’t helping these children. Think about what’s happening in psychiatric hospitals, which are closing down, not even accepting people who have attempted to take their own lives, let alone those with eating disorders. State-sponsored therapy is now very limited, and in this case, we’re talking about expensive medical treatment, because when you have to treat the whole body, these costs multiply. I would like to help these people. I have a lot of ideas for projects I would like to do. I’m currently looking for a collaborator. The Foundation has been in existence for a short time, two years, and at the moment it provides reliable information and is a source of knowledge about eating disorders. Because like I said at the beginning – you have to get out of this information chaos to know where to look for help.

Author: Monika Tutak-Goll

Karolina Otwinowska – President of the Głód(nie)Nażarty (glodnienazarty.pl) Foundation, psychology graduate of the University of Warsaw, author of memoirs about her own struggles with eating disorders titled “Dieta(nie)życia” [Diet of (No) Life], “Historia mojego (nie)ciała” [The Story of (Not) My Body]; “Głód(nie)Nażarty” [(Un)fed Hunger]; winner of the 3rd place at the Polish Art Festival “Orzeł 2016” [Eagle 2016], screenwriter; the originator of an educational programme based on her own experiences, acquired knowledge and the needs of her readers – people suffering from eating disorders and their loved ones.

Illustration: Marta Frej

The text was published in wysokieobcasy.pl on 27 March 2021