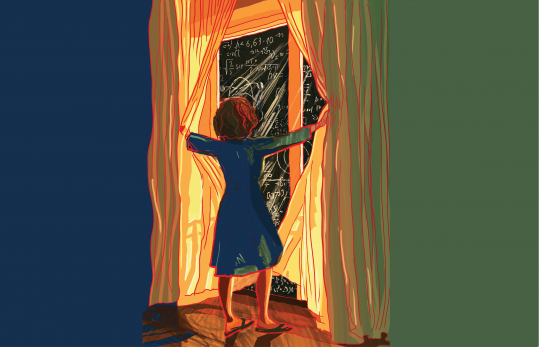

I will measure the universe with a ruler

How do you win (as the first Polish woman) the Lodewijk Woltjer Prize awarded by the European Astronomical Society?

I’m just trying to measure the universe.

With a ruler?

The problem is that measuring the universe is done with different rulers. And different measurement methods give slightly different results. So we are faced with a conundrum: does this mean that any of these methods are not accurate? It may turn out that the model of the universe with the so-called cosmological constant, which was introduced by Albert Einstein, does not work. Which would mean we have to have new physics. Because physics, despite appearances, is not at all a fixed thing. Physics (in fact, science in general) is divided into a well-established part, contained in textbooks, and the other part – the most interesting for scientists – which has not yet been developed. Some people work purely theoretically, that is, they sit and think. I test by observing. Hence the idea of measuring the universe. As a precaution, we apply the concept of dark energy, more general than the concept of a cosmological constant, to these studies. Dark energy can be constant or it can change. While I admit that it is a catchy name, it is not clear that it definitely changes over time. My recent work focuses on this aspect – one of the methods that allow us to measure the rate of expansion of the universe. We aim to develop a map of how the universe is expanding. We just need to find an adequate new ruler for accurate measurements.

Is there a male and a female physics? Do men engage in sitting and pondering, and women choose hands-on observation and measurement, as you did?

Perhaps there is something to this. I, however, don’t see much difference. Everything is basically based on maths and equations. On the other hand, there may be differences in work style. Statistically, women are less feisty, brag less, and therefore their ideas are often quoted by men rather than by themselves. They don’t insist on making their mark with their presence, ideas, and scholarly output. Women are more modest, which works against them.

In recent discussions about women in science, it has been emphasised that even if there are a lot of female doctoral students in a field of study, there are far fewer of them reaching the rank of professor. And that’s actually been the case for years.

I support young women of science, but a miracle will not happen. The situation for a woman scientist, if she decides to have a child, is quite different from that of a man. I think it’s even more logistically difficult for women in science now than it used to be. Making a career in science means, among other things, that after graduating from university and getting a PhD in Poland, one goes abroad for a so-called postdoc. If a woman is in a steady relationship, she is unlikely to rely on a man to keep her company. Of course it happens, such as when a man is a freelancer. In most cases, the partner is more likely to say: ‘I’m not going with you. What will I be doing there? You can take the kids and go’. Finding work for yourself and your husband for three years in one country, for three years in another one is very challenging. Not everyone can handle it.

And what did your career look like?

I have had two employers over the long years, so I am not a work ‘jumper’. I started while I was still an assistant professor at the Nicolas Copernicus Astronomical Centre in 1978. When I was trying to get my PhD, I heard: ‘But you’re not suitable’. Only Professor Bohdan Paczyński believed in me. Unfortunately, he passed away in 2007 and doesn’t know that I received this award. He was the one who saw that I had potential and offered me a position as an assistant. It was from him that I learned how science is really done.

How is science really done?

Let me tell you: in college, you acquire some knowledge, but before a PhD, you feel confused because you don’t know what to actually do. Professor Paczyński showed me: ‘If something surprises you, you need to find out what’s underneath it. You have to draw it first’. We sat and drew. Black holes, disks, Saturn’s rings... As we drew, we thought about the observational implications and whether in fact the thing we were drawing might exist. If we thought the picture looked promising, we started creating equations that could describe it. Counted exactly what you should see when observing the object. If the calculations did not match – we went back to the image and modified it. You often have to do very complicated numerical calculations to make the results accurate.

If there was no Professor Paczyński, how would you have managed to convince the world that in a few decades you would be inventing new tools to measure the universe?

I don’t think I would have made it. I would have worked for a scientific publisher. And maybe that’s where I would have worked until retirement. It was after this lack of support at university that I started working at the Wiedza Powszechna publishing house. I thought it would stay that way, that I had no chance in the scientific world. But I still went to the astrophysics lectures given by Professor Paczyński. He noticed I was taking notes. He asked me to compile them – that way we would have an almost scientific article. I compiled the notes, but in my own way and actually brought him my concept of the lecture. He said: ‘This is not my lecture, sign it with your name and send it to the “Postępy Astronomii” [“Progress in Astronomy”] quarterly. But in that case – why don’t you go back to the university?’. If it wasn’t for that gesture on his part, I wouldn’t have fought for myself because I wouldn’t have had the motivation. It’s hard to find it when you’re 25 years old, you can’t yet do research on your own, and you’re being told that you are unsuitable.

Do you see in your doctoral students the 25-year-old Bożena of years ago?

I certainly don’t tell anyone that they’re unsuitable. I point out that not everyone is talented in the same direction. Astronomy is a wonderful field where different talents come in handy. Someone may have an aptitude toward working with large databases. There are people with an aptitude for theoretical work who can work on a topic that interests them. Some people love to work in large groups and such groups also operate in the astronomical world – they include a hundred or even a thousand people. In astronomy, you should always pay attention to your aptitude and make the best of it. Currently at the Centre for Theoretical Physics of the Polish Academy of Sciences we are looking for young researchers to join scientific teams, I encourage them to apply.

Did you know as a teenager that physics would be your future?

Would you believe that my physics teachers did everything to discourage me from it? By pure chance in high school, I came across a popular science book called ‘Mr Tompkins in Wonderland’. Absolutely fascinating. It showed me that physics really does touch on important subjects. I then became interested in the concept of time and space. It fascinated me that time moves forward and in space you can go left, right, forward, backward. In the general theory of relativity actually these things get mixed up and sometimes in time you can go backwards and in space you can only go forwards. I thought: I’ll study physics, then in college I’ll learn how it really is with this time and space. Then I found out that my professors only answer it with equations, because they themselves don’t know how it is with this time and space thing. I eventually devoted myself to astrophysics.

Do you look up at the sky sometimes without the awareness of the equations, the astrophysics? Just like that, romantically?

Rarely. Then all I can really recognise in the sky is Orion, the Big Dipper and a few other objects.

Professionally, I have been regularly observing in South Africa with a SAT telescope for over 10 years. I observe quasars, which are some of the brightest objects in the universe. In fact, I don’t even see the telescope, I order the observations, and they last three quarters of an hour each.

Why are quasars so important to you?

In some sense, quasars are important to all of us. Every galaxy must go through a juvenile stage and we observe its activity in the form of a quasar. This is a fairly short stage, but at the same time extremely important to its entire life. This is when the most stars are formed. Unnecessary matter then flows to the centre, at the same time the black hole grows. If it grows too much, the rate of matter flow will be very high – at this point stars stop being born. The galaxy later freezes. Right now we don’t have a quasar in the immediate area.

Do you believe in life in other galaxies?

It’s hard for me to say that unequivocally. On the one hand, the universe is huge: one hundred billion galaxies, and in each one a hundred billion stars. There seems to be plenty of opportunity to develop life. And on the other hand, the universe, when observed, is incredibly empty. Of course, the distances between stars are much greater than the star itself. The distances between galaxies are also considerable. Atoms are kind of empty, too – just tiny atomic nuclei and electrons around. Billions of stars and billions of possibilities for life to arise, billions of universes and this one of ours, private, just for us – it could have happened this way too. It is possible that there are more universes, we don’t know that. You have to look around. I’m still optimistic – after all, just 200 years ago we didn’t even know there were other galaxies. Now we see our universe exactly to the end. We are aware that we are sitting in a bubble of microwave background radiation. What we now have to do is look closely to see if this bubble is even. Maybe it’s curving somewhere? Perhaps it is uneven? I feel that as Earthlings we are taking a kind of inventory of our universe. Still incomplete, it will still take some time. But with the help of gravitational waves, it will be possible to look deeper than before. I don’t rule out the possibility that it will turn out: the bubble we live in is not so even. Or we may even see traces of this bubble interacting with another bubble. Then it will mean that maybe a whole new opportunity opens up.

What has been your enlightenment in physics in recent years?

The most important unsolved mystery is dark energy. This is new. For me, I am most passionate about the quasar model that I developed 11 years ago. This is a relatively new proposal, not everyone is convinced yet. This model – to simplify – is that a quasar, having a black hole at its centre, produces a sort of sandstorm on the surrounding accretion disk matter. This is my original idea. It looks very spectacular because the matter glows with a very distinctive light created just by illuminating the sandstorm. I hope to convince more people of the validity of this model. Although some of the people who have been working in this field much longer repeat: ‘It can’t be that simple’. Obviously these are men, and as a result, some of them simply do not quote me.

Are they jealous?

Maybe. I take comfort in the fact that the younger the men, the more often they quote me, so I believe there is a generational shift going on in science – more pro-women.